As we explored in last week's installment, in Surveiller et Punir Foucault offers a critical account of the Enlightenment's darker side. According to him, scientific rationality found its greatest social application in the surveillance and in the management of life, the education and the disciplining of humans, in short, orthopaedia.

Correcting humans' imperfections by means of science is a singularly modern (and Western) enterprise. It has its benefits, or its utility I should say: it is no surprise that utilitarian philosophy arose in late 18th-century England. That particular type of collective pedagogy aimed to root out deviancy and to produce armies of interchangeable and compliant workers, so as to spread happiness, of course. It achieved this by training subjects to discipline themselves on their own, in the secret of their conscience, in order to rectify their moral defects. It was as much a coercion of the body as it was a coercion of the soul. It bred “normal,” healthy bodies that consented and conformed.

To Foucault, this was the key discovery of modern power, the one thing that distinguished it from more archaic strategies of social control. In his view, and contrary to popular belief, scientific rationality had failed to liberate humans. Overall health and well-being might have improved, utility might have been maximized so to speak, but that was precisely the objective of the newfound technologies of power, to raise bodies fit to work and fit to consume. In a way, it is as if Foucault had decided to pull the curtains to convince us that Huxley’s Brave New World was not just satire but something very real and tangible, a historical process unfolding among and, more importantly, within all of us.

Foucault's pessimistic understanding of progress has been debated at great lengths. For instance, liberals were aghast given that their normative totem is the triumphant march of the individual person’s formal rights. For their part, Marxist thinkers were not amused: none of this left much room to class struggle as the engine of history. Prospects for the proletariat’s emancipation dwindled to a trickle.

However, it is striking that no-one seems to have embraced Foucault's theories with more gusto, albeit unwittingly, than Utopian capitalist tech lords and other sundry futurists and space colonialists.

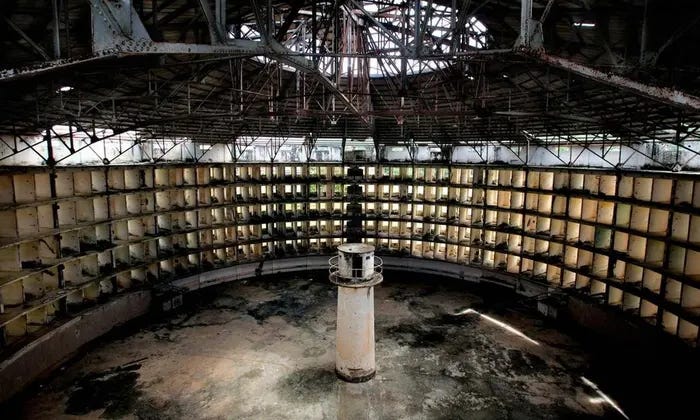

Their Utopia is an updated, high-tech version of Bentham’s panopticon. In space habitats, in orbit or on Mars, all your vital signs will be constantly monitored, all your bodily secretions will be probed and quantified, all your movements will be recorded, supervised and optimized. Your daily activities will be planned and regulated to ward off the worst of physiological degradation. You will have to religiously attend to the needs of the machines that preserve you from death. Your freedom to wander about will be curtailed because in space, there is no outside. You will be like Seinfeld’s bubble boy, forever living inside of a fitbit and strapped to convoluted breathing equipment.

Space colonialists see no problem with that, let alone evil. They welcome it. Petty data collection and permanent surveillance are integral to their Utopia. They are necessary procedures for safety and survival, engineered to allocate scarce resources and to make the starships run on time.

But remember, this is a panopticon. Taken in isolation, the sci-fi gadgetry and the architecture of surveillance are uninteresting. They only matter insofar as they are instruments of discipline, that is, master keys to the space inmates’ souls. Their function is not merely to keep the confined subjects alive under extremely hostile environmental conditions, but also to induce them to reform their morality.

The space colonists must accept their own subjugation. They are the colonized. They must internalize the supreme authority of the agents, mechanical and social, that feed and maintain them. And furthermore, they must rejoice at this. In their surrender to platitudinous abstractions, “preserving the light of consciousness”, “fulfilling human destiny” and all that drivel, they must feel a sense of greater existential duty, they must display gratitude and elation. Industriousness, moralistic self-improvement and indeed, virtue, are the panopticon’s true purposes. The reasons put forth for building such correctional facilities are each loftier and more altruistic and more progressive than the next one. They are in fact completely irrelevant. On Earth as in orbit, these penitentiaries are but means to an end, and the end is well, penitence and jubilant self-sacrifice — what Étienne de La Boétie once called “voluntary servitude.”

(On a side note, it is endlessly bizarre and distasteful to this bookish Frenchman that, in the English-speaking world, La Boétie would be some kind of minor token of Libertarian thought, such as it is; the incorrigible Murray Rothbard even wrote the introduction to the standard English translation.)

But wait, there’s more.

The Utopia of space colonization encompasses both the individual, the inner self, and society as a whole. In order to colonize you must populate. And in order to populate you must copulate (at least that's the state of the art for now). On paper, notionally, space colonization is the purest depiction of biopolitics, the disciplinary, technological management of human populations. That is where, unbeknownst to them, space colonialists draw closest to Foucault.

Space colonialists are earnestly hoping to build new and better worlds for others to live in. Their beliefs are sincere, for such is the nature of faith. At the same time, they do grasp the challenges of establishing permanent human settlements in space, places where people will procreate for generations and generations. They are aware that healthy reproduction is the paramount burden of any space habitat or colony, and that space actively wants to kill us. The ultimate success or failure of their dream hinges upon fit, able bodies and functioning genitalia. Thus, their seemingly urgent task is to reshape entire human populations to make them fit to reproduce in unlivable surroundings. That is precisely why they hatch detailed proposals for medical experimentation, racing to “innovate” increasingly depraved and obscene solutions to non-existent problems. For instance, one man-professor with impeccable credentials and government funding (who self-identifies as an “effective altruist”) waxes poetic about splicing tardigrade genes into future space humans. Well, sir, be my guest, but you go first.

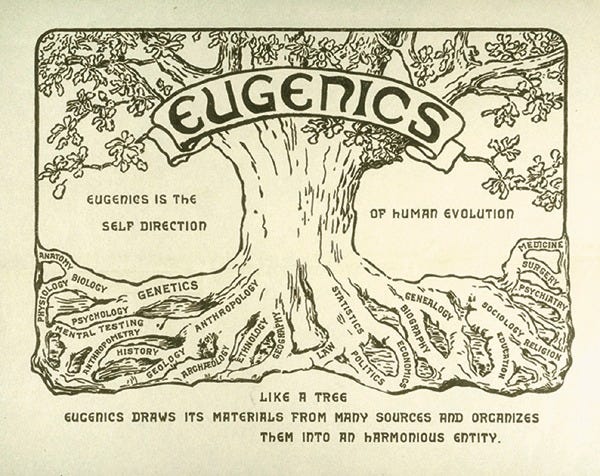

If you set aside the faculty club’s wannabe space Mengeles, it remains that all this amounts to corrective education, orthopaedia, but for the species — or rather, for the chosen, hypothetical few who would elect to leave Earth forever. It’s as if the faint prospect of space colonization gave today’s elite scientists permission to speculate anew about barbaric interventions on human bodies and human heredity without any hint of remorse. It is the return of the (barely) repressed, eugenics, all in the name of spreading our seed to the stars.

To these well-intentioned humanitarians, humanity is an unruly child in need of tutoring. Progress is the patient reformation of the body and the soul under the stern guidance of science.

It bears repeating: every Utopia is a theory of education. Unsurprisingly, pedagogical metaphors haunt space colonization literature, from the Russian Cosmists to Carl Sagan. They are often couched in the guise of stupendous concepts — think of Vladimir Vernadsky’s “noosphere,” the putative realm of the universe-spanning mind that one day will supersede the physical limitations of humanity and of Earth (the “biosphere.”) Transhumanism truly is the Phenomenology of the Spirit for peddlers of greeting cards.

These melancholic utterances pervade the many treatises and perorations of the space colonialists. They are ethically unmoored, casting humans as immature and docile novices waiting to be molded and primed for a chimerical destiny amidst the void of the heavens.

That is one way to deal with modernity’s regime of surveillance and biopolitics. Capitulate before it, become its most craven advocates and never miss an opportunity to call for the (moon) boot of space capitalism to stamp on humanity’s face forever.

I know which side I’m on. What about you?

I think there is a fundamental disconnect between the space utopias of the capitalist space colonialists and the space utopias of the average fan/enthusiast/dreamers. There is a big difference in perception of time and realistic change in technology.

The space panopticon of monitoring and the dependence on the machine and the surrender to the system of power and control are very much real, in the short term. Barring some transformational technology actual space colonization will be cramped, smelly, medically horrible and subject to the eugenical and controlling whims of the SpaceBros, to be sure.

But the average enthusiast ignores that phase of space utopia history [which is likely to be the only phase for centuries or millennia or forever]. Instead, they envision their role in the space utopia as fundamentally different and occurring after that initial phase of sitting in a cold Martian hut or the tedium of being a cook or mushroom farmer at the L5 colony. Ignoring that dreary reality, they think they and their descendants will be the Belters from the Expanse, anarchist communes with their own ships and fusion drives. They think that they will be the freedom fighter Maquis captain or wandering space archeologist adventurer, not the quasi-military lower-decker stuck cleaning the shuttlecraft toilets on a Federation starship. *They* will certainly be Han Solo, not some Empire bureaucrat stuck in a cubicle.

All of those visions of the future require some magical technical advancement - the fusion drive, warp travel/replicators, or magical hyperspace drives and droids and the like. I think that there is just a fundamental misunderstanding of the future and the likliehood of technological change on the part of the average person. The average person thinks of space and dreams that they will be the main character in a world with no practical limitations on travel/vehicle ownership/resources, but really they would be the NPC toiling in the space factory.

The SpaceBros, in a way, think the same thing, but envision themselves achieving main character status in the near term. They will have the nice moon suite with the windows and the private room on the Mars shuttles. They will have the shielding and the clean water that the NPCs prepared for them. They will replicate their life in a California estate but in SPACE, farther from those pesky poors they see when the limo driver takes them to the airport. They won't have to see the support system.

The odd thing is that both groups can actually achieve their dreams here on earth. The SpaceBro can get the fancy yacht and float in the Pacific or Mediterranean in air conditioned comfort. Or maybe head to their New Zealand Bunker and live the life of the space colonist, but with simpler toilets. The poor space-grunt can get a shaggy dog and a a truck and smuggle drugs, living that Han Solo life, or maybe head to Ukraine to join a rag-tag band of freedom fighters and fight The Empire. Nothing is stopping some would-be beltalowda from getting an RV or sailboat and starting a mobile anarchist commune doing iterant mining and construction work.

I'm really enjoying these articles, but have grown increasingly hostile to Foucault. The appeal of Discipline and Punish relied on the implicit assumption, very prevalent in 1970, that a radical and positive libertarianism, including, for example, the abolition of criminal justice systems, was a real and current possibility. As that failed, Foucault gravitated towards ordinary US-style propertarianism, of the kind popularised by the Chicago School in Economics.