It is not uncommon for space colonization enthusiasts to claim that “colonization” is the wrong term for their pie-in-the-sky enterprise. We are told that “colonization” hearkens back to dark episodes in history and that in space, thankfully, there are no natives to despoil, exploit or mass murder. It is different this time and therefore, accordingly, it should not be called space “colonization.”

Space archaeologist and author Alice Gorman kindly provided me with a perfect example of that whitewashing rhetoric. It is lifted from her twitter feed's replies:

The Polynesian metaphor stands out.

The poster (or rather, the reply-guy) marshals it to preempt charges of Euro-centrism. And for good reasons: space colonization propaganda overflows with oafish paeans to Columbus, the so-called “Age of Discoveries”, “Enlightenment”, manifest destiny and such (we’ll come back to that later). By contrast, it is hoped that comparing space colonization to the Polynesians’ dispersal into the Pacific Ocean will cancel out the ravages of European racism and imperialism. By evoking Arcadian vistas of pristine, tropical islands and the great voyages across Moana, one hints that it is different this time, or at least that it should be.

The metaphor is itself an old story. It replicates in every way the fascination of 18th century European philosophers for the dwellers of the South Seas, these Utopian “noble savages”, not yet corrupted by civilization, who lived in harmony amidst the bounties of Creation. In that particular retelling of the myth of space colonization, there will not be any genocide for the sake of political or economic advantage. On their hegira into the vast ocean, the Polynesians only found uninhabited archipelagos. Thus, settling planets and asteroids like islands in the heavens will be peaceful, perhaps even a rebirth and a cleansing, a tabula rasa, the chance to start afresh and to return to our original state of nature or, in other words, a shot at redemption.

That alternate, idiosyncratic justification for space colonization comes to us straight from a pioneering and esteemed anthropologist of Polynesia, Ben Finney. It first emerged in 1985, in a volume he co-edited with astrophysicist Eric Jones: “Insterstellar Migration and the Human Experience.”

Ben Finney was a scholar of surfing and navigation. Starting in the late 1950s, he had made it his mission to prove that Polynesians had indeed settled the islands of the Pacific. This went against popular beliefs at the time. It was thought that Polynesians were descended from South American people. In 1947, Norwegian adventurer and professional fabricator Thor Heyerdahl had built and sailed the Kon-Tiki from Peru all the way to the Tuamotus. The documentary film of his exploits had even won an Oscar in 1952. It was all bunk.

Along with artists, craftsmen and colleagues at the University of Hawaii, Ben Finney built a sailing canoe according to traditional Polynesian techniques (double hull outrigger, crab claw sails). They recruited one of the last way-finders, Mau Piailug, from the Micronesian island of Satawal. Piailug guided the ship, Hōkūleʻa, on a journey from Hawaii to Tahiti in 1976. To reach Tahiti, 4,000 kilometers to the South, Piailug did not use any clock, map or modern navigation instruments, only the stars, the sun, the winds and the shape of the swells.

Mau Piailug, Ben Finney and their Hōkūleʻa crewmates, most of them young Kānaka Maoli (or native Hawaiians), showed that the ancient Polynesian art of way-finding was not a legend but a practical, living knowledge (for more on this, I strongly recommend Sam Low’s beautiful 2019 book: Hawaiki Rising: Hōkūle‘a, Nainoa Thompson, and the Hawaiian Renaissance). Hōkūleʻa confirmed that not just Europeans could sail across the open seas and against prevailing winds. Eventually, by the late 1970s, it was acknowledged that Pacific Islanders had done so, and much more extensively. Contra Thor Heyerdahl’s fabrications, they had stretched all the way to Hawai’i, Aotearea and Rapa Nui or, as its inhabitants call it, Te Pito o te Henua - the navel of the world.

It was finally possible to imagine a story of human exploration and diffusion that did not draw on the usual fare of conquest and violence, Christopher Colombus, Captain Cook, guns, germs and steel (to allude to another all-too-famous fabulist besides Heyerdahl).

As Finney and Jones write in their introductory essay for “Interstellar Migration…”:

By A.D. 1000, the Polynesians and their Micronesian cousins, probably the first people to sail into the heart of any ocean, had discovered and settled just about every inhabitable island within the vast Pacific… (Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience, p. 21)

They opine:

Today, because of continued economic and technological growth, we stand on the threshold of space. Although it may be easy for some to dismiss the dreams and designs of colonizing space as mere extensions of Western imperialism or of technological thinking gone wild, we maintain that the urge to expand into space is basic to our human character. We are the exploring animal who, having spread over our natal planet, now seeks to settle other worlds. (Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience, id.)

In short, Finney and Jones enroll the unsuspecting Polynesians, who most certainly did not ask for this, in their fantasy of space colonization. The Islanders’ exploration and settlement of the Pacific Ocean, all achieved without recourse to European technology or science, are trotted out to deliver the incontrovertible evidence of a more universal, biological instinct (or “urge”). It is not imperialism, it’s “human character.” All this for that.

An astrophysicist reducing ancient practices and traditions to atavistic, hereditary traits is not unexpected. To the hammer everything looks like a nail. But Finney? A respected anthropologist, the one who had helped build Hōkūleʻa and who had sailed on its maiden voyage? From him, of all people, such magical thinking is both incomprehensible and inexcusable.

Readers will not have missed the semantic slippage from “exploring” to “settling other worlds”, as if one led to the other as a matter of course. Kick the Euro-centrism out and it comes back through the side door.

But the more consequential insult, however, consists in ascribing deterministic, biological causes to unique, contingent and inherently social activities. It’s nature vs. culture for dummies. Jones and Finney hail the genius of the Polynesian explorers in order to better erase their unique ingenuity and to strip them of their history and of their agency (to use the parlance of our time). The Islanders’ patient and dogged transmission of astronomical science, their craft and their inventions of the outrigger canoe and the crab claw sail (the first known sea vessel that could tack into the wind), become mere stages in a grander morality play, humanity’s foreordained journey of progress. Ad astra, yet again.

That ideological flimflam drapes the decrees of our rulers and oligarchs in eschatological poppycock. The mundane and the pedestrian — incremental improvements in rocketry, the thirst for power and affirmation, the vulgar prod of greed — are thus recast as instruments of our species’ destiny, an epic uplift that spans evolution and geological aeons. We shall inherit the stars, whether you want it or not. Now move along, serfs.

The Polynesian expansion is still shrouded in mystery. For instance, archaeological finds suggest that at some point between 500 and 0 B.C.E, the people who ventured into the Eastern Pacific abandoned pottery, arguably the most advanced technology of their time. The Lapita Complex does not extend beyond Fiji and Samoa. Progress, it would appear, does not march in a straight, upward line.

Similarly, a recent international genomics study has uncovered evidence that Polynesian explorers reached the coast South America at least once, and then travelled back to their pelagic homeland:

…We find conclusive evidence for prehistoric contact of Polynesian individuals with Native American individuals (around AD 1200) contemporaneous with the settlement of remote Oceania. Our analyses suggest strongly that a single contact event occurred in eastern Polynesia, before the settlement of Rapa Nui, between Polynesian individuals and a Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia… (Alexander G. Ioannidis et. al. Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement, Nature, 2020)

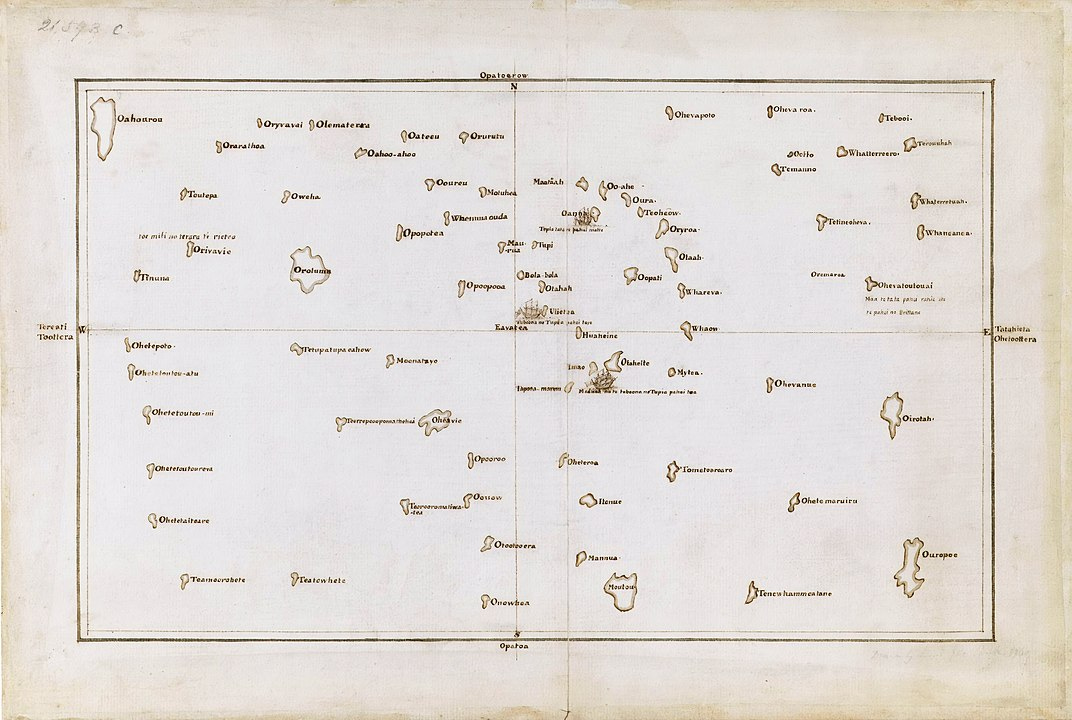

We do not know the exact motivations and circumstances that prompted the first wave of migration from Samoa and Fiji to the Society islands. We do not know why, afterwards, some groups of Islanders maintained tight circuits of mutual exchange while others chose isolation after settling in new places. Regular commerce between Tahiti and Hawaii seems to have ceased entirely some time during the 13th century, but that is not certain. We know from the journals of Georg Forster, who accompanied Cook on his first voyage, that high priest and navigator Tupaia could locate from memory all the Society islands, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, and that he could converse fluently with the inhabitants of New Zealand. We do not know why those who landed on Te Pito o te Henua did not pursue further relations with the rest of Polynesia, even though they were more than able to. Similarly, we do not know why Māori navigators may have attained the edge of Antarctica long before Europeans did, but did not consider sailing back and forth to the much closer Society Islands.

It is a fool’s errand to divine a vindication of human nature in the buried treasures of an illustrious people — whose history is barely understood because of genocide. To tout a blueprint for space colonization off the backs of survivors is not only frivolous but cruel and fraudulent. The Māori have a proverb, “Tuia i te here tangata”: thread together the many strands of people. It is a call for friendship and the recognition that our lives are all intertwined. To this day, they are more charitable and forgiving than our own ancestors ever were.

Remains the single remotely cogent point of comparison between space colonization and the voyages of the Polynesians.

Space, like the Pacific Ocean of yore, is devoid of humans. You could even say that it is one of space’s defining characteristic. And just like in the Pacific, there is nobody out there to displace, replace or kill. Ergo, it could never be colonization in the old, loaded sense of the term.

This is all dandy and convenient, especially for the apologists of a more gentle and more liberal kind of space colonization. It’s also plain wrong.

Let me rewind.

Over millennia, Pacific Islanders had learned to fashion not only ocean vessels but entire landscapes. They were consummate astronomers, geologists, botanists and agronomists. Keen observers of the Earth and the heavens, they had developed an abiding intimacy with their processes. It is not solely navigation. Hawaiian lore, for instance, records the ancestors’ uncanny understanding of plate tectonics. It is not formulated in the language or the logic of Western science, but rather in the incarnated drama of myths. It is nonetheless accurate, as far as describing the westward movement of the plate over Hawaii’s volcanic hot spot.

The Polynesians’ expansion into the Eastern Pacific was methodical and sweeping. They were gardeners and ecological engineers. On every island they landed, they would channel streams and build artificial ponds to grow taro and to farm freshwater fish. They would transplant and acclimate breadfruit, banana, pandanus and coconut trees. Accounting for local variations, the same crops, the same trees, the same animals are found everywhere from Raiatea to the Marquesas, Rapa Nui and Hawaii. As a result, even the low estimates for the population of pre-colonial Tahiti, the Marquesas and Hawaii show densities equal if not superior to that of England in 1801. Where today’s tourists see untouched nature, it is only because the orchards and the irrigation works were reclaimed by forests after those who tended to them had died en masse.

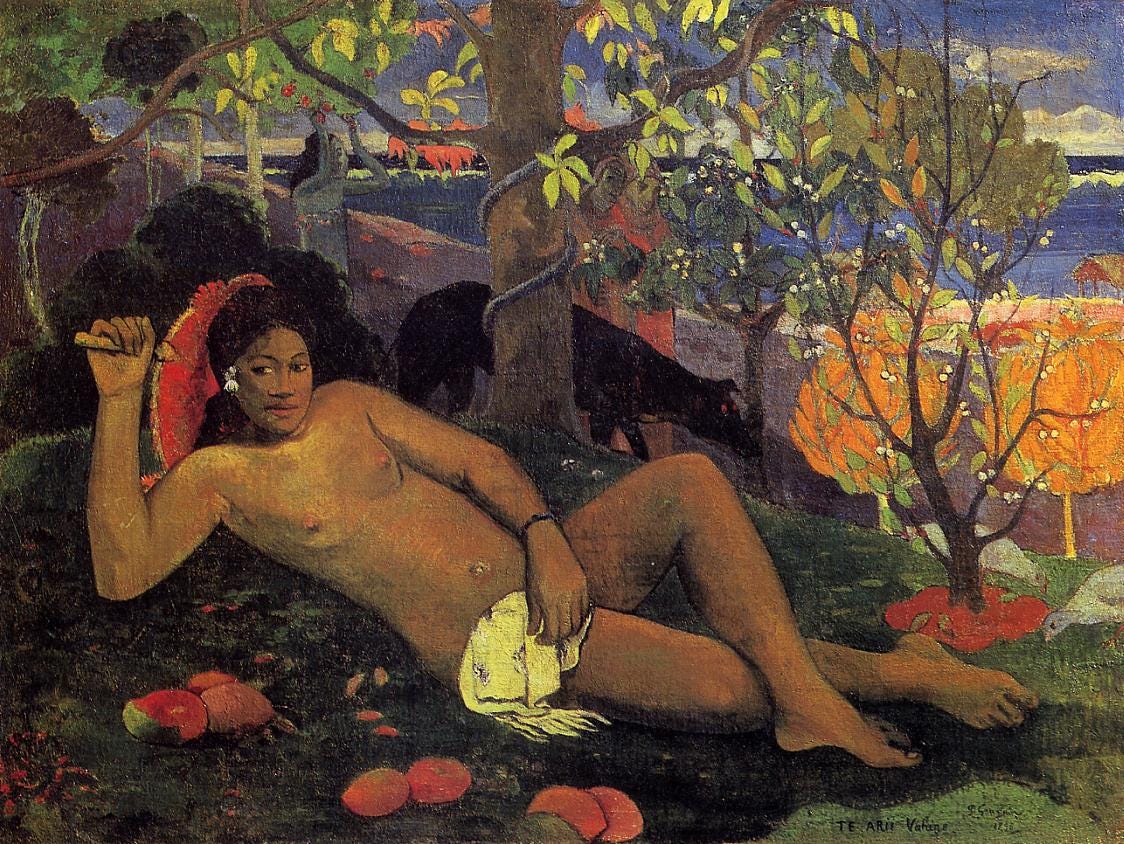

The apparent cornucopia of the Islands required continued coordination on a large scale. Pre-colonial Polynesian societies thrived mainly due to their rigid, hierarchical organization. The commoners, the majority of the people, labored on the land. At the top, the high-born, the ali’i or ariki caste, collected the surplus and wielded absolute political power. Meanwhile, the priests (kahuna in Hawaii, tahu’a in Tahiti) were responsible for spiritual and worldly knowledge, and the enforcement of taboos. A few Polynesians were of noble extraction. Many others were not. None of them were “savages.” European explorers, mesmerized by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, believed they had stumbled upon paradise. In reality, the Polynesians’ displays of effortless opulence, their licentious mores — oft-discussed in the salons of Paris and London — were the exclusive privilege of chieftains and kings.

Polynesian navigators plucked islands from the ocean’s horizon and on them their ari’i established new fiefdoms and new lineages. Commoners would plow the fields at the behest of their seigneurs. There may not have been native inhabitants to subjugate or to colonize on these new islands, but for all intents and purposes the Polynesian colonists were themselves the colonized. They toiled in bondage to priests and kings, who promised in exchange to defend the land from rivals and to protect it from the gods’ wrath.

At least, there was always the chance to abscond, to flee one’s assigned condition. You could prove your spiritual power, or mana, in war, or you could jump in a canoe headed for the great yonder, to start over on another speck of volcanic rock yet to be fished from the swells.

When invoking the Polynesian experience, the proponents of space colonization make the same error as the Enlightenment’s salon philosophers. The exhilarating freedom they think they see in the Islanders’ great voyages of exploration is precisely the freedom that was denied to most commoners. They mistake the prerogatives of the dynastic few for the will of an entire people.

In addition, even if space colonists will encounter no-one in the murderous emptiness of the heavens or in the arid plains of Mars, unlike their Polynesian forerunners, they will never be able to escape their serfdom. The capricious machines that provide life-support, and those who own and operate them, will always demand constant toil, propitiations and sacrifices. Space colonists will spend their entire existences strapped to contraptions that monitor and restrain them. In space, as in the islands of the past, the colonists will be the colonized. However, in space there will be no outside, no bodily autonomy, no open ocean beyond the reef and no circumventing the sovereignty of machines. Space is where ecological freedom dies.

Despite the insatiable appetites of their kings and the harshness of their taboos, Polynesians knew full well what they owed honua, the Earth, and makani, the wind. They knew they owed them life and the fleeting freedom to break away from their overlords.

Today’s space colonialists know of no such things, or forgot them, or ignore them.

Let it be their undoing.

BONUS: a powerful documentary on Mau Piailug, featuring Ben Finney, Herb Kane, Nainoa Thompson and Mau himself (mentions the tragic death of Eddie Aikau).

A minor point on the intellectual history. I always understood that settlement from Asia was the dominant view, and that Heyerdahl's expedition was an effort to support a minority view. On this way of reasoning, Finney's expedition showed that it was technically feasible from either direction, leaving the issue to be settled by other arguments, which favoured Asia.